From ecotourism to enclaves in Costa Rica

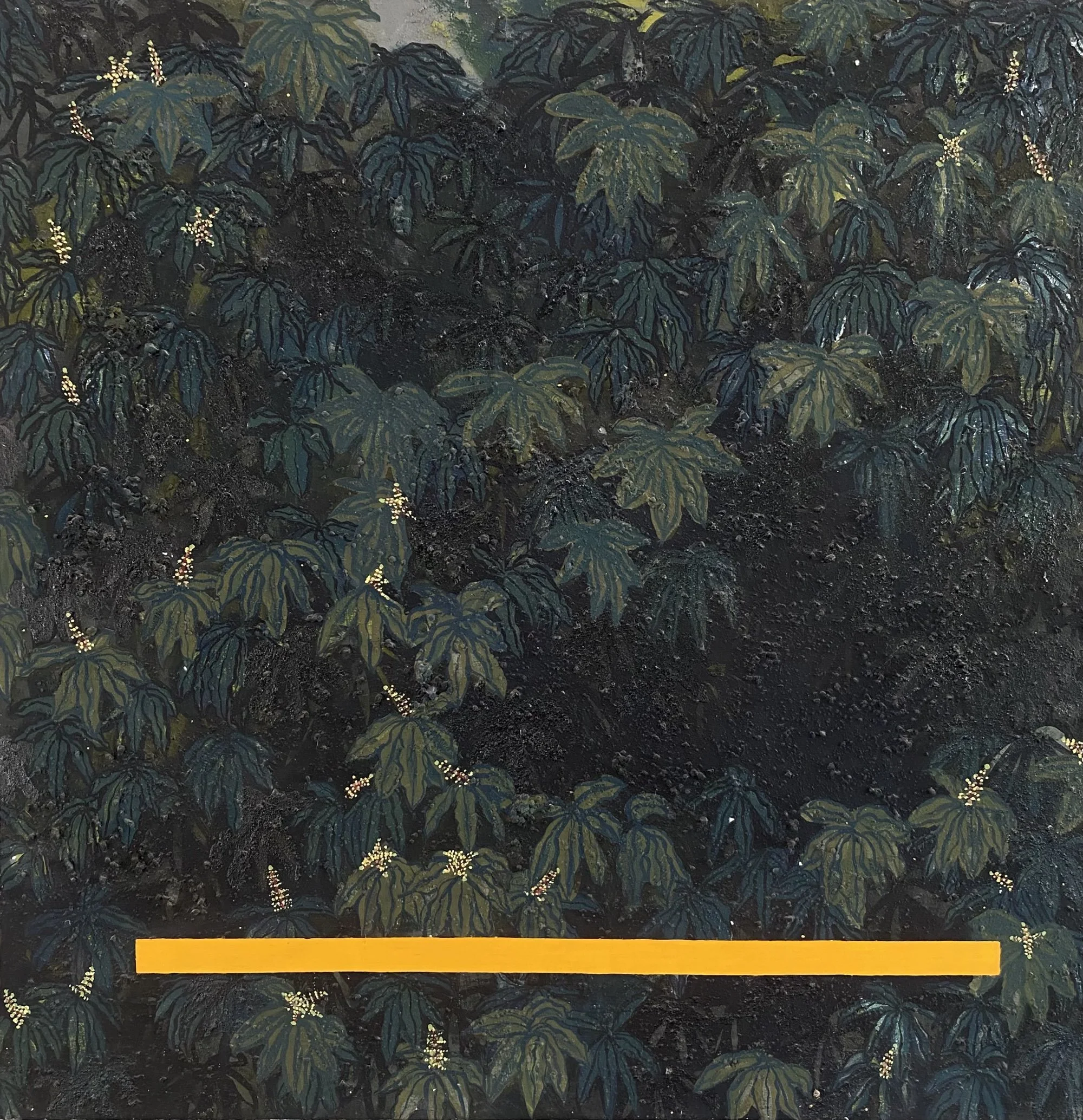

“Mango,” Acrylic, 2022, 80x80cm © Bhiany Guzmán (@verteselva).

Opinion • Liz Carrigan • February 5, 2026 • Leer en castellano

Guanacaste sits in the northwest of Costa Rica, near the border with Nicaragua, where the Pacific runs out along a rugged, sun-bleached coast.

Black sand beaches carry the imprint of volcanic origins. Rivers cut through dry forests and savannas, lakes gather in basins, and national parks protect a dry tropical ecosystem, a unique bioregion that begins in Mexico and stretches to Guanacaste. For decades, this landscape has been celebrated for its natural beauty and held up as a model of environmentally conscious living.

That promise has drawn waves of visitors in search of the jungle and a gentler rhythm of life, but it has also drawn capital. Along the coast, dirt roads are now lined with English-language “for sale” signs. SUVs kick up dust as they pass gated entrances marked by palm trees and private security.

Behind high walls, luxury homes rise in landscapes historically tied to local livelihoods, even as those ways of making a living are increasingly displaced. The language of sustainability is everywhere, while everyday life in the region is increasingly shaped by water scarcity and rising living costs.

These pressures have surfaced as socio-ecological conflicts, particularly around water, where rural communities confront state-backed tourism and real estate developments over access to increasingly scarce resources.

The image of Guanacaste as an untouched paradise is a selective narrative. Since the 1970s, it has been promoted through state tourism campaigns and reproduced by real estate firms, short-term rental platforms, and luxury developments. The visual script rarely changes: beaches appear empty, landscapes uninhabited, nature stripped of social life.

Alejandro Alcázar Fallas, an activist with the Colectivo Antigentrificación, described Costa Rica’s image as a paradise as an illusion. “Costa Rica has been sold, or presented, for many years, decades, as a separate phenomenon, as if it were an island,” he said in an interview at the end of last year. “We are between Panama, which was a territory occupied by the United States, and Nicaragua, a country with long histories of internal conflict and revolution.”

This narrative of exceptionalism, according to Alcázar Fallas, feeds directly into the idea of Costa Rica as an ecological paradise. “That imaginary of Costa Rica as a paradise, something that even sounds biblical, is an imaginary that is useful for the tourism industry because it ensures that people keep coming and buying into that idea, into that product,” he said.

And though it is cast as a democratic and ecological oasis standing apart from a region scarred by violence from the Contra war of the 1980s onward, Costa Rica shares many of the same inequalities and structural continuities as its neighbours, including its peripheral place in the global economy and its dependence on extractive industries, tourism among them.

Exceptionalism, carefully maintained

Tourism has undeniably reshaped the region around Guanacaste. But a related and more pernicious transformation has unfolded alongside it. Since the early 2000s, and accelerating after the COVID-19 pandemic, Guanacaste has become a destination for lifestyle migrants and digital nomads, largely from North America, whose presence shapes the local economy and land use.

As public and communal spaces are privatized, the visual and spatial landscape is changing abruptly. Beaches that once felt shared are reorganized around commercial use.

Families who have lived and worked in these areas for generations find themselves priced out or displaced, while those sustaining the tourism economy struggle to survive on low wages. Migrants, mostly from neighbouring Nicaragua, comprise close to 10 percent of Costa Rica’s population and underpin the essential services that sustain more privileged forms of migration in Guanacaste.

Neoliberal reforms have made it exceptionally easy for foreigners to purchase property in Costa Rica, granting buyers almost the same rights as citizens, with no requirement for residency or long-term ties. A passport is enough.

This has turned land into a speculative asset, drawing real estate capital toward beaches and formerly communal or public spaces. Along the coastline, gated communities now proliferate. Using Google Maps, I’ve tabulated more than 20 in Guanacaste alone. This reflects a form of enclave development in which land and everyday life are shaped by outside economic interests rather than local communities. Lifestyle migrant amenities range from luxury resorts tied to North American and Spanish hotel chains to residential enclaves of condominiums, golf courses, and marinas.

Housing developments for lifestyle migrants continue to creep into environmentally sensitive landscapes, despite regulatory frameworks that formally require coordination between central and local authorities as well as water, planning, and environmental agencies to protect them.

Paradise is not empty

Housing has become a central site of inequality for young people across Latin America, where affordability is eroded by speculative development and limited economic mobility. In Costa Rica’s coastal regions, this precarity is exacerbated by the arrival of lifestyle migrants.

Patri, a local resident who was forced to move inland due to rising rents and now commutes long distances for low-paid work, offered a stark account of life in Nosara, which is both a town and district that’s become a popular destination for yoga practitioners. “It’s not easy to find housing here. A dignified, safe place costs around 700 dollars a month,” she said in an interview on January 7 in Nosara. “That’s what I earn in a month.” Both women I interviewed in Nosara asked me not to use their last names due to privacy concerns in the small town.

Tourism-led development rests on the promise of stimulating the economy and creating jobs. But job creation, in practice, has come to mean maintaining the infrastructure of other people’s abundance. In Guanacaste, employment has grown fastest in accommodation and food services, alongside construction and real estate tied to this expansion. By 2021, these sectors dominated the regional economy. Much of this work sits at the lowest end of the wage scale, with women concentrated in the most precarious service roles.

“I have a Master’s degree, I’m bilingual, and I came with years of experience,” said Daniela, who worked as a teacher at an international school in Nosara. “And still, when I arrived, the reality was that the salary wasn’t enough.”

In Nosara, these pressures are particularly acute. Daily life is shaped by precarious work conditions. Underemployment is rife, and the jobs available marginalize local workers, while those employed in service roles often feel “their hands are tied,” according to Alcázar Fallas, who says they are reluctant to report abuses for fear of being fired or excluded from future work.

Patri described how this spatial reorganisation is experienced in everyday life. “Nosara is a highly exclusive place,” she said. “It’s not for all types of tourists. There are no spaces where locals and expatriates or visitors really mix.”

Even infrastructure, Alcázar Fallas suggested, has been shaped by logics of exclusivity. “For a long time, foreigners who arrived in the seventies, mostly from the United States, opposed building paved roads, because difficult access allowed them to keep that ‘paradise’ isolated, that pristine place where only a few people could go,” he said.

But for workers, the absence of infrastructure is a daily risk. Nosara has no public bus service. “That forces people to buy motorbikes, often without licenses or permits,” Patri said. “Employers require that you can get to the workplace, but there is no minimum transport system here. That results in many motorcycle accidents and deaths.”

What is called development reorganizes everyday life around serving consumption from elsewhere. Transient wealth circulates through rentals, tourism, and services, while social and environmental costs remain local.

As capital searches for new frontiers, land is turned into assets and folded into distant markets. Wages cannot keep pace. Homes are priced beyond everyday life. What makes the system effective is also what makes it destructive, and nowhere is that more clear than in northwest Costa Rica.

Last Sunday’s victory of a populist, right-wing president in Costa Rica can be read as a response to widening social inequalities intensified by tourism-based development models, which concentrate wealth while excluding many from the gains of growth.

AUTHOR BIO: Liz Carrigan is a researcher and writer examining development and unequal forms of mobility in the context of the climate crisis.