The revolutionary roots of Pride in Mexico

Photo collage by Ojalá based on photographs by Ricardo Balderas.

Reportage • Ricardo Balderas • June 29, 2023 • Read in Spanish

Bodies bathed in glitter and sweat come together in Mexico City’s heavy summer heat. It’s the last weekend in June, and united by slogans, they walk together to the largest plaza in the country, their many flags conveying many things, and one thing: fiesta. Difference. Excitement. The exaltation of yet one more expression of what it means to be human.

One day of freedom a year, in exchange, perhaps, for the appeasement of a mass of people who are increasingly submerged in Mexico’s late and lagging democracy.

Few if any of the 250,000 people who attended this year's LGBTTTIQ+ pride march in Mexico City are familiar with the event’s backstory. It’s understandable: documenting and transmitting social processes has always been a challenge.

History has an old habit of fragmenting the memory of those who took the first steps. Six steps, a hundred steps, two legs. The first time Pride took place in Mexico was on July 28, 1978. One thousand people attended.

How did we go from persecution and madness to slogans? Through struggle. So began the first public demonstration of the population of sexual diversity in Mexico.

"There really is a first public appearance of these collectives... Initially we have the appearance of a small group of people from [sexual and gender] diversity, mainly gay men and trans women or effeminate people," Kenlly Pacheco, who coordinates one of the Organizing Committees of Mexico City’s Pride, told Ojalá. "The first event was related to the 10th anniversary of the massacre of student comrades in 1968, and from there, well, it began to have a large media impact."

Pacheco explains how disinformation and stigma in the media and academia fuelled early pride marches, either by spreading fear and misinformation about AIDS or by publicly ridiculing those who do not comply with the heteronormativity.

Two fronts are recognized as having initiated this multitude: the Homosexual Revolutionary Action Front (FHAR) and the Lambda Group for Homosexual Liberation (LAMBDA). Both emerged in the 1970s against totalitarianism, heteronormativity, homophobia, machismo, racism and classicism.

A file on the FHAR signed by the head of the DFS. Photo: Ricardo Balderas.

The FHAR comes out of a shared heritage with the French workers' movement, in alliance with that generation’s feminist movement, including the Movement for the Liberation of Women (MLF). Its slogans consistently highlighted the struggle against the bourgeois and heteropatriarchal state.

The encounter between the student struggle of 1968 and movements for the civil rights of sexual and gender diverse people created an amalgamation between workers' struggles and those of members of sexual and gender dissidence and minorities.

With the help of people like Juan Jacobo Hernández, Salvador Novo, and to a lesser extent Carlos Monsiváis, José Joaquín Blanco, Juan Soriano, Luis González de Alba, López Páez, Roberto Espejo (La Gorda Espejo) or Máx Mejía Torres, poems and essays were written, and lectures were given all over the country on the class struggle and its relation to the segregation of those who did not inhabit sexual norms.

This is how the myth that the Mexican government would later focus on so much was born. Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, Luis Echeverría and José López Portillo, Presidents who were in power from 1964 to 1982, considered this level of social organization to be a threat and a danger that threatened good customs. They began to hunt down revolutionary queers.

One by one, the spokespeople of the rebellion fell victim to a state that spied on militants from Mexico’s homosexual left.

The files of repression

On February 6, 2020, hundreds of documents (more than 10,000 boxes of them, to be precise) were transferred from the shuttered facilities of the Federal Security Directorate (DFS) to the warehouses run by those who safeguard Mexico’s historical memory.

Among the documents were files collected by Mexico’s spy agencies over the course of their surveillance of sexual diversity movements, as well as those the gendarmes labeled "resentful communists."

Among thousands of documents, Ojalá was able to identify at least 51 activists, poets, writers, thinkers, journalists and even police officers, who, according to some documents, belonged to leftist movements that promoted the recovery of civil rights in relation to sex and gender diversity.

Click here to download the database of DFS surveillance of LBGTTTIQ+ people and collectives

Of the files analyzed by Ojalá, 257 deal specifically with persecution individuals belonging to the LGBTTTIQ+ community or one of its collectives. They tell of persecutions that occurred between 1926 and 1985, the period covered by the documents. The main fear of the DFS was criticism of the bourgeois state.

During Luis Echeverría’s government (1970-1976), the Institutional Revolution Party (PRI) created the White Brigade, a paramilitary group whose objective was to surveil any group that represented a threat to the social order, which is to say, leftist or communist collectives.

These files, pulled from the innards of the National Security offices, contain records of meetings that took place in nightclubs, during academic conferences, and communication via telephone calls and in printed publications. There are photographs and even detailed information about the places where the community freely expressed their sexuality.

The surveillance by the White Brigade was part of an illegal counterinsurgency operation, in which centrally organized paramilitary groups worked to inhibit political participation via military violence. The documentation of this process of repression is housed at the General Archive of the Nation (AGN) and the National Institute of Historical Studies of the Revolutions of Mexico (INEHRM).

Over this period, the Mexican government had aspirations of absolute control of the movements that were bubbling up in society. It seems that there was always a spy, a policeman or an informant willing to give up the peace for a little bit of cash. The two most surveilled cities were Guadalajara and Mexico City.

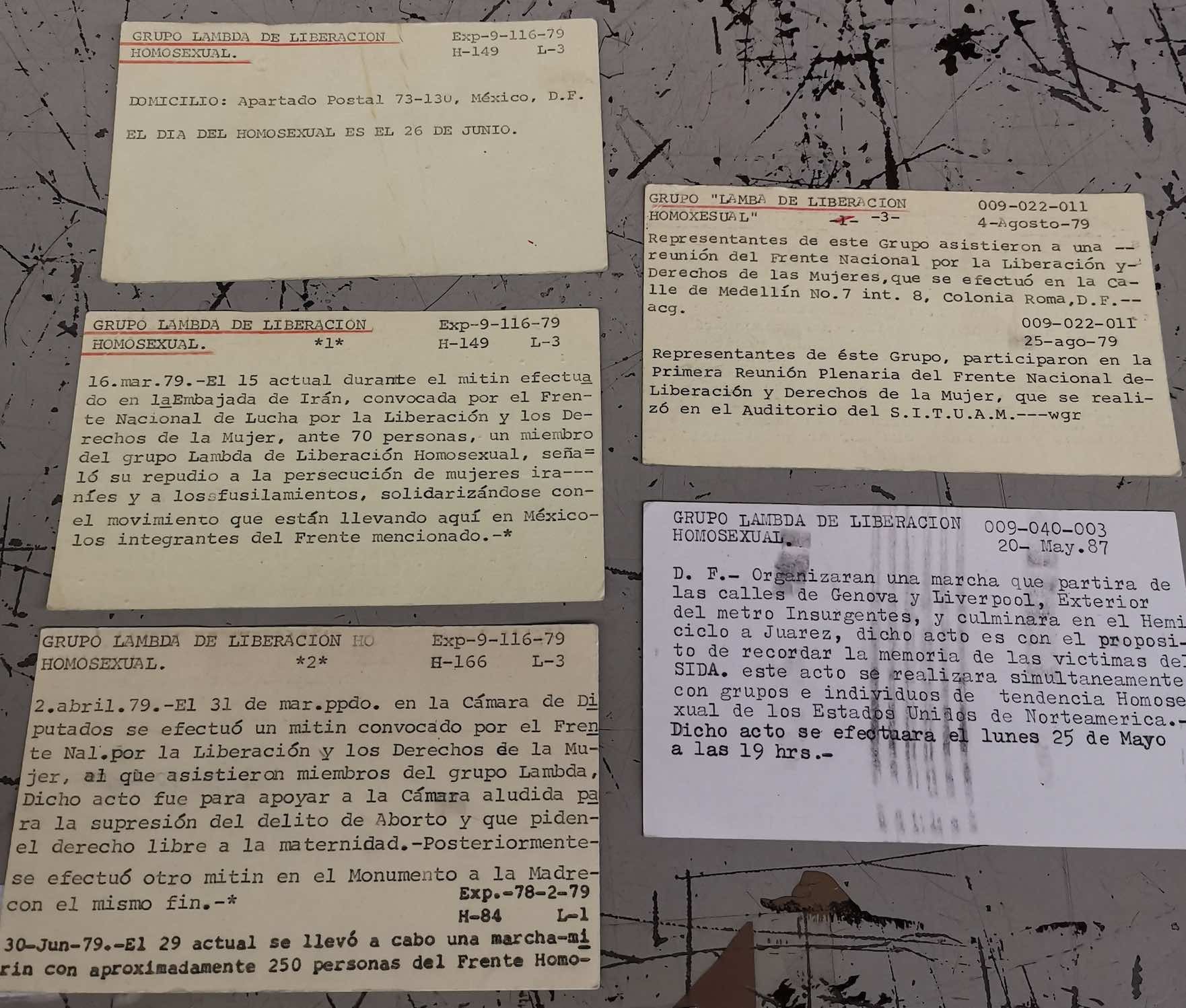

Information sheets about LAMBDA. Photo: Ricardo Balderas.

The documents reveal, at first glance, familiar problems and prejudices.

They contain rank homophobia, machismo, and the criminalization of behaviors considered immoral at the time. The fear of anything demonstrating society’s capacity to self-organize is manifest.

The files are shot through with stigmas about prostitution, fear of discussing differences and class struggle, and false medical discourses of that era, like the notion that Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) was exclusive to queer people.

On the LAMBDA Group:

May 20, 1987. DFS notes: The Lambda Group for Homosexual Liberation organized a march that will begin at Genova and Liverpool streets outside the Insurgentes metro station, and end at the monument to Juárez, this act commemorates the victims of AIDS. This act will take place simultaneously with others by groups and individuals with homosexual tendencies in the United States. The event will take place on Monday, May 25 at 7:00 pm.

On prostitution:

January 05, 72. DFS reports: Raúl Saunas, located on Fray Bartolomé de las Casas on the corner of Toltecas. Independently of the service it provides, it is used as a brothel, women of the gallant life, without any modesty are introduced to these bathrooms where they exorcise their carnal instincts, in addition marijuana is trafficked.

On FHAR:

June 20, 1979. DFS reports: On the 19th of June, in front of the Guatemalan embassy in Mexico, located at Vallarta No. 1, Col. San Rafael, Mexico City, a rally was held, called by the student committees coordination of Mexico City, the purpose of which was to repudiate military aid from the Republic of Guatemala to the government of Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua, during which Carlos Toymin, representative of this front (FHAR), expressed his solidarity with the struggle of the Nicaraguan people and invited those gathered to the march. I [sic] encouraged participants to:

1.-Act in solidarity with women’s struggles.

2.-Connect among progressive groups.

3.-To use class analysis to constantly discuss and clarify the link between our sexuality and our economic, political and social activities.

The documents described above are part of what are called "information sheets." They were part of an internal DFS protocol meant to generate information about people the military or police at the time considered to be of interest, or saw as alleged threats.

If the organization or person in question was of further interest to senior police commanders, the files got more in-depth. The more in-depth files are missing or were destroyed along with documentation on some of the victims of forced disappearance.

A quarter million walk in the history of resistance

Civil rights can be won, but they can also be repealed.

It is true that fights such as equal marriage, prohibition of conversion therapies, and access to gender reassignment and legal abortion, have led to legalization—albeit in an an unequal way—in different states of Mexico.

It is also true that an ecosystem unfavorable to the struggle for civil rights for queer people in Mexico has emerged. This ecosystem is made up of transphobic groups, extremist religious organizations and conservative millionaires who push an anti-rights agenda, and it presents new challenges for gender and sexual dissidents. Pacheco thinks now is a good time to look to the past, because by analyzing repression over time we can build a more supportive community.

"It is utopian to think of getting to the point—and maybe we won’t live to see this— when the Pride march will no longer be a matter of making demands. Instead it will be a celebration," said Pacheco. "The invitation [to participate] is always open. In past years comrades belonging to unions have participated, and not necessarily only those belonging to a political party."

What has changed over time is organization. On Saturday June 24, the XLV Pride March was held in Mexico City and it included the participation of more than 40 civil society organizations. They sought to "recover the social, plural, non-partisan and cause-based sense of the March", according to a June 19 communiqué.

This year, people living with disabilities led the march.

It has been 38 years since the last file was created by a state thirsty for control. Since then, the political and social conditions have not changed much, and neither have the slogans.

This year, in addition to making demands related to gender and sexual diversity, the march communiqué called for an end to the "machismo and discrimination that exists within the LGBTTTIQA+ population, for inclusive and stigma-free holistic healthcare, for an end to hate crimes, in particular of transfeminicides and the complete lack of justice for victims, and the need to keep working to prohibit heteronormative therapies."

So it is that the volunteers who organize the LGBTTIQ+ Pride March in Mexico City continue serve as guardians, gargoyles who watch from the streets in the Zona Rosa and walk down Reforma Avenue. It is they who—sometimes without realizing it—are the guardians of Mexico’s history of pride and resistance.