Feminist art under fire in Santa Cruz, Bolivia

Reportage • Dawn Marie Paley with photos by Josune Palenque Aponte • April 28, 2023 • Leer en castellano

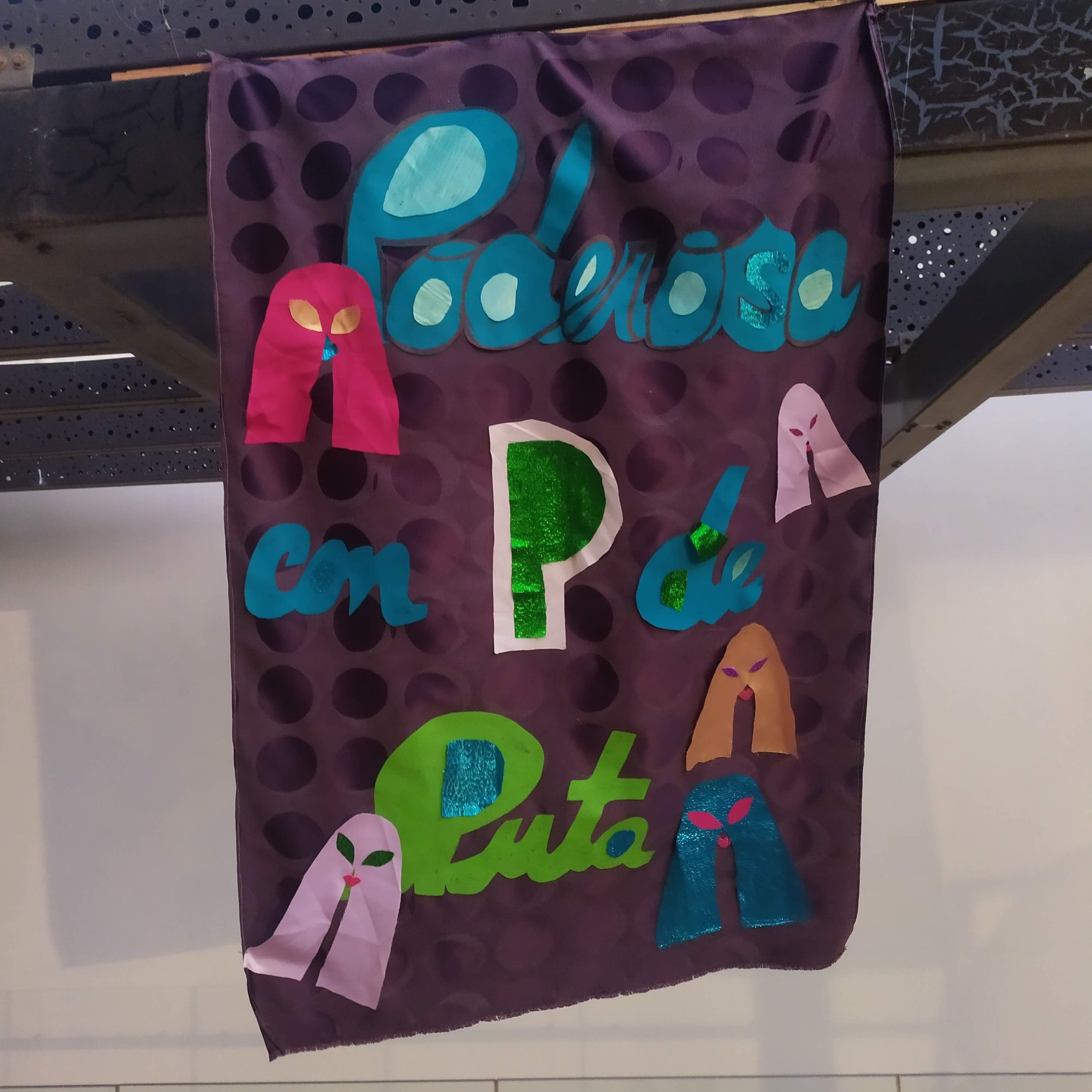

This past February, feminist artists from the Por Pluma Cultural Space in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, launched a call to create a series of banners to bring to the March 8th march. Following the march, the artists and city officials had agreed to display the banners in the courtyard of the Altillo Beni City Museum.

The banner making workshop started on March 5, when the women sat down with textiles, objects, scissors and thread. What was perhaps most interesting what what emerged from the process of creation.

"The main idea was to hear all different voices, that each would convey their political objectives, or their wounds, through the creation of their own message," said Nelly Vázquez, a poet and artist who is a member of Por Pluma.

First they drafted texts to be written on the banners, opening a dialogue among the women gathered. The themes that emerged were powerful, ranging from family secrets to abuses within the church. Then they began to sew. The women also composed a song, using art to respond to the particularly difficult political conditions in the city.

Months earlier, a civic strike-blockade was held in Santa Cruz, through which the political and business elite of the region tried to force the hand of the national government.

For autonomous feminists in Santa Cruz, the civic strike represented the rise of a civic dictatorship, underpinned by the fascistization of daily life. In interviews and conversations, they told me that when the national government imprisoned Fernando Camacho—the governor of the department—in December, there were some disturbances, but that the people were worn out from the impacts of the disruptive civic strike.

In this context—with the conservative right governing at the departmental level, and the conservative left nationally—feminist organizing is not easy.

By the time March 8 came around, the group of 16 women who had shared their pain and created posters together had built a sense of mutual trust. They were eager and nervous to show their artwork to the world.

That day, the women of Por Pluma gathered with many others in the city’s downtown. It was one of the city's largest International Women’s Day mobilizations in living memory.

"We were super happy," Vázquez told me in an interview at the Museum of Contemporary Art (Maco) in Santa Cruz last month. "We felt as though we’d scored a major goal."

After the march, they took their posters to the City Museum. Over the following weeks, they were installed in the courtyard. The exhibition opened on March 21, and the next day everything went as expected: people came through to see the exhibition, some snapped a selfie.

Nothing seemed out of place at all.

But in the early hours of March 23, a brusque message arrived via WhatsApp: the banners must come down immediately.

Vázquez, and fellow Por Pluma member Nadia Callaú, headed to the municipal offices to understand what was going on. Before arriving, they put on their mascaritas, traditional face coverings worn by poor and working-class women during the city's carnival for over one hundred years.

They spoke to a secretary, who told them that she had no meeting scheduled with anyone wearing a mascarita. They gave her their names and were let in.

"They never told us why the expo was shut down," Vázquez said. The women found out later—through informal channels—that two banners, one that says 'Powerful with a P for Prostitute' and another that says 'Abortion is Love' bothered a friend of the city’s Director of Culture. That’s why she ordered the exhibition removed, revealing another ultra-conservative facet of the city.

In 1999, the City of Santa Cruz tried to censor a painting of a nude Virgin Mary (thin, white and without pubic hair). But that time, the battle against censorship of art was won and the piece remained in the city’s Cultural Center.

Last year, anti-rights protestors broke into an exhibition called Pride Revolution that commemorated sexual diversity month, also at the City Museum. According to curators, people showed up shouting slogans that were "full of discrimination, homophobia and misogyny," and destroyed the artworks.

"It seems like we’re going back to the era of drug trafficking, to the 80s, when they wanted to censor everything," Vázquez said. "How is it possible that we’re regressing so much?"

"They’re the children of Camacho," stated Callaú, who is also an artist. She’s referring to the local government, that wants to dictate what is art and what isn't.

At this same meeting, the City offered them a space in the courtyard of the MAC. While they were negotiating the terms of the new space, municipal workers entered the City Museum and removed the banners.

When I spoke with Vázquez and Callaú, they were preparing to hang the banners at the MAC. Nearby, in the exhibition halls, there was a display of artwork that was provocative remixed by curators as part of the Santa Cruz International Biennial of Visual Arts.

One of the pieces was the painting censored in 1999. It had been intervened by other artists with a transparent plastic film painted with pubic hair. The artist, who had led the fight against censorship more than 20 years earlier, complained about the intervention before destroying it and exposing his penis in front of attendees.

"We’re living in the Middle Ages," Vázquez said. And she said it not once, but several times over the course of our interview. Greg Abbott's Texas (where some public employees were notified that they have to wear clothing that reflects their 'biological gender'), Ron DeSantis' Florida (where the state congress is trying to abolish drag performances) and the reversal in reproductive and sexual rights across the United States came to mind immediately.

Santa Cruz isn’t the only place where it feels like the Middle Ages are returning.

Nevertheless, the women of Santa Cruz continue organizing and creating. They insist that feminist art and creation have a place in all kinds of spaces.

"When you understand contemporary art, you understand that is feminism’s lover. Both have the same goal: the destruction and dismantling of hegemonic power," Vazquez said. "Contemporary art cannot be understood without feminism."

After repeated guarantees and promises from city officials, Por Pluma’s exhibit at the MAC was called off. They’re now planning to display the banners in the city’s streets.