8M in Cochabamba: feminist, anti-fascist, and full of life

Opinion • Claudia López Pardo • March 20, 2023 • Leer en castellano

Libertador avenue starts at the edge of downtown, on the other side of the Cala Cala bridge. It connects the city center with the part of Cochabamba that, in times of war, becomes a bastion of para-police groups mobilized in response to political polarization.

When war is latent, violences are activated and deactivated according to patriarchal pacts between the state and other political-corporate figures in confusing ways.

As Cochalas (women from Cochabamba), we have found it helpful to name war and its violences.

Right there, where Libertador Avenue starts, just outside of Félix Capriles Stadium, stands a monument to the athlete. On the morning of March 8th, the statue was redecorated. From its waist hung a purple sign that read “8M: the feminist era.” On its back, a qhepi (a package wrapped in cloth) and in its hands, a wiphala and a feminist symbol. A purple handkerchief was wrapped around its neck.

A local paper reported on the redecoration of the statue for 8M. The rebellious action echoed other iconoclastic actions throughout Bolivia in recent years.

When I heard the news, my face lit up with a smile. I was preparing to go to the occupaction, an occupation and call to action convened outside the public university.

Photo by Clauida Lopez Pardo

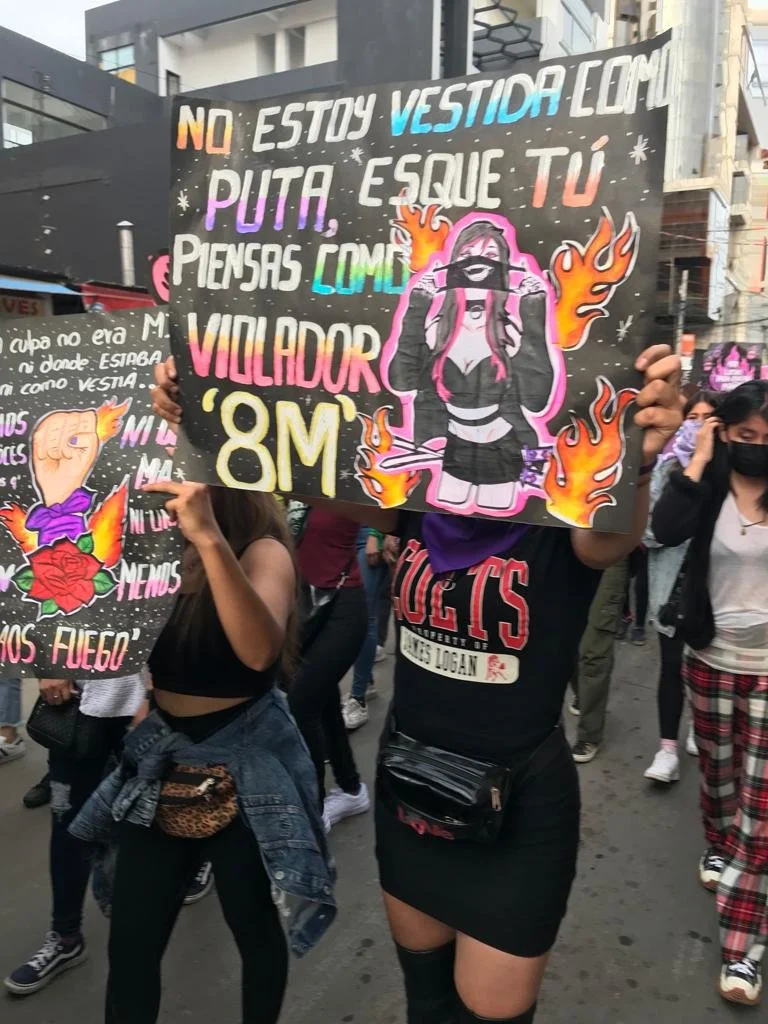

The autonomous feminist occupaction–non-institutional and non-partisan–was filled with colors and hardworking hands. It kicked off with a twerk class, in homage to the great, subversive and sinful vulva that the younger women had created. It was here that all of the collectives and groups of women who participated in 8M came together before the march. (Earlier in the day, an institutional march had left from inside the campus).

One of the most interesting aspects of the occupaction was the response to the call to create protest signs: young women came together to adorn their signs with incredibly creative slogans. The one that stood out to me read “Our struggle is so important even the introverts are here.”

The mobilization began just after five o’clock and took the shape of a powerful river of women, lit by the falling light of sunset.

Glitter glowed on the faces of the youngest women. Most of us wore black, purple and green.

Photo by Claudia Lopez Pardo

It was hard to see the full size of the march. All kinds of women marched, some in large and small groups, others in pairs, mothers walked with babies and there were many small children. Older women also joined the march, having just finished their workday.

Our meeting was a self organized encounter, and the way we came together was a complete break with the way activists usually organize in Bolivia. The women didn’t parade, they mobilized. They chanted and yelled, holding up their signs and smiling among each other.

Photo by Claudia Lopez Pardo

At the head of the march were four women carrying a banner with this year’s slogan: In the face of fascist violences, the feminist era. In another section, a batucada [Afro-Brazilian inspired percussion] of diverse femmes raised our spirits and occupied the streets with all their force.

The march arrived at the courts, and there was an action held by families and those accompanying survivors of patriarchal violence in the face of state injustice. Along the edge of the march, the self-defense commission closed the streets to traffic, creating chaos in downtown Cochabamba.

Before this year, no 8M march had ever gone beyond the center or north of the city.

This year we took the streets towards the south, opening up, sending a clear signal of belonging and breaking with the stigma cast upon the south of the city.

The flow of mobilization marked the city, through collective presence and actions, and the communal production of language and power.

The graffitis, tags and condemnations in the wake of the march signaled a limit to injustice, to the impunity produced by institutions, and to everyday violences. The walls of downtown read like the intimate diaries of the youngest women, exposing to the public a kind of emotionality that took the form of denunciation, of escrache (public calling out of an abuser), and the desire for repair: “[the patriarchy is] going to fall,” “complicit,” “murderers,” “rapists,” “corrupt,” “attackers.”

Photo by Claudia Lopez Pardo

The graffitis and the paste ups were similar, but not exactly the same. They’re a loud way of demanding justice. A call to memory in a country where the state and patriarchal pacts encourage forgetting.

What is expressed in the streets must be taken seriously. In our revolution, anger isn’t created, it’s inherited. There is no turning back, and we know that being in rebellion is healing.

This year, after visiting various locations, the mobilization ended in San Sebastián Plaza. The flow of women and dissidents stopped in front of the women’s prison to call out to incarcerated women, affirming that prisons are an extension of the injustice against us.

“Forcing women into precarity and leaving us without choices, with pitiful wages and exhausting days is economic fascism,” read the statement pronounced at the end of the march.

The words were echoed by the sign hoisted by a young woman. It read: “I am not low wage labor.” The clarity of the slogans illuminate a moment which calls on us to name and defend women workers, in order to transform everything else.